Posted To: Ideas & Innovation > Blogically Thinking

Posted To: Ideas & Innovation > Articles

First published Nov. 23, 2015 on Mediashift.org.

Jan Schaffer co-authored this report with Mimi Onuoha, a Fulbright-National Geographic fellow and data specialist, and Jeanne Pinder, founder of ClearHealthCosts.com, which crowdsources medical costs.

When CNN recently announced it was ending its longstanding iReport crowdsourcing efforts to, instead, source stories directly from social media streams, it was a notable marker signaling how news organizations are making different choices about audience growth and engagement.

It also affirmed the findings in our Guide to Crowdsourcing, released Nov. 20 by Columbia’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

As far as engagement around creating content, our team saw two paths clearly emerging: One involves news organizations investing major resources into inviting and organizing input from their audiences. The other involves culling non-solicited contributions from social media to help either create a story or identify story ideas.

The label “crowdsourcing” has been applied to both. Indeed, the term has become conflated with many things over the last decade. Some regard all story comments as crowdsourcing. Others apply it to any user-generated content, distributed reporting, collaborative journalism, networked journalism, participatory journalism and social journalism as well. To be sure, all of these share attributes.

Our task, we decided, was to zero in on journalism efforts that involve specific call-outs. Then, through interviews, a survey and case studies, we developed a new typology to spotlight how journalists are using crowdsourcing. The team included me, Mimi Onuoha, a Fulbright-National Geographic fellow and data specialist, and Jeanne Pinder, founder of ClearHealthCosts.com, which crowdsources medical costs.

OUR DEFINITION

Here’s our definition: Journalism crowdsourcing is the act of specifically inviting a group of people to participate in a reporting task- — such as newsgathering, data collection, or analysis — through a targeted, open call for input, personal experiences, documents, or other contributions.

Using that definition, we found that most crowdsourcing generally takes two forms:

- An unstructured call-out, which is an open invitation to vote, email, call, or otherwise contact a journalist with information.

- A structured call-out, which engages in targeted outreach to ask people to respond to a specific request. Responses can enter a newsroom via multiple channels, including email, SMS, a website, or Google form. Often, they are captured in a searchable database.

We assert that crowdsourcing requires a specific call-out rather than simply harvesting information available on the social web. We believe that the people engaging in crowdsourcing need to feel they have agency in contributing to a news story to be considered a “source.”

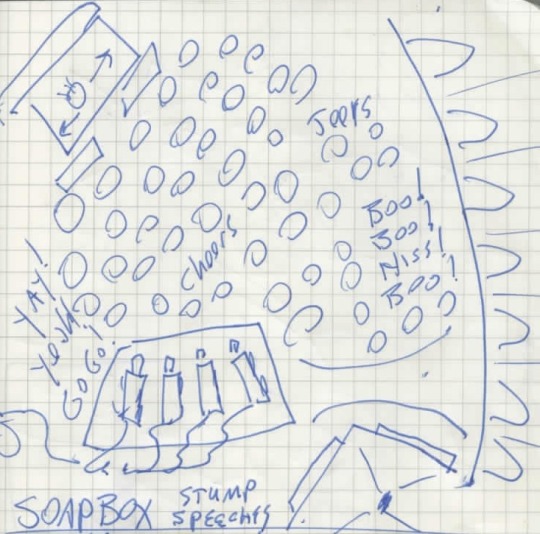

While crowdsourcing efforts don’t fit neatly into classifications, for this guide, we’ve organized our typologies by six different calls to action:

- Voting — prioritizing which stories reporters should tackle.

- Witnessing — sharing what you saw during a breaking news event or natural catastrophe.

- Sharing personal experiences — divulging what you know about your life experience. “Tell us something you know that we don’t know.”

- Tapping specialized expertise — contributing data or unique knowledge. “We know you know stuff. Tell us the specifics of what you know.”

- Completing a task — volunteering time or skills to help create a news story.

- Engaging audiences — joining in call-outs that range from informative to playful.

We found that crowdsourcing has produced some amazing journalism. Look at ProPublica’s efforts on Patient Safety, political ad spending, or Red Cross disaster assistance. Or check out The Guardian’s efforts to chronicle people killed by police in the U.S., or track expenditures from Members of Parliament. See what WNYC has done to map winter storm cleanup. Or look what stories listeners wanted CNN Digital’s John Sutter to do in its 2 Degrees project on climate change.

Crowdsourcing made all these stories possible.

It has also made journalism more iterative – turning it from a product into a process. It enables newsrooms to build audience entry points at every stage of the process — from story assigning, to pre-data collection, to data mining, to sharing specialized expertise, to collecting personal experiences and continuing post-story conversations on Facebook and elsewhere. Moreover, experienced practitioners are learning how to incrementally share input in ways that tease out more contributions.

We see how today’s crowdsourcing would not be possible without advances in web technologies that have made it easier for journalists to identify and cultivate communities; organize data; and follow real-time, breaking-news developments.

Journalistic Tensions

Still, crowdsourcing produces some tensions within the industry, Some journalists worry about giving the audience too much input into what their newsrooms cover. Others fear the accuracy of the contributions citizens make — a concern that long-time crowdsourcers dismiss. Many investigative reporters, in particular, recoil at telegraphing their intentions through an open call for contributions.

Others balk at committing the resources. Crowdsourcing can be a high-touch activity. Journalists must strategize about the type of call-out to make, the communities to target for outreach, the method for collecting responses, and the avenues for connecting and giving back to contributors to encourage more input. That is all before the contributions are even turned into journalism.

We found that, for all its potential, crowdsourcing is widespread and systemic at just a few big news organizations — ProPublica, WNYC, and The Guardian, for example. At other mainstream news organizations, only a handful of reporters and editors — and not the institutions themselves — are the standard bearers.

Crowdsourcing and Support for News

There are intriguing clues that there is a business case for crowdsourcing. Indeed, some crowdsourcing ventures, such as Hearken and Food52, are turning into bona fide businesses.

For digital-first startups, in particular, crowdsourcing provides a way to cultivate new audiences from scratch and produce unique journalism. Moreover, once communities of sources are built, they can be retained forever — if news organizations take care to maintain them with updates and ongoing conversation

Amanda Zamora, ProPublica’s senior engagement editor, credits their crowdsourcing initiatives with building pipelines directly to the people who are affected.

“We are creating lists of consumers interested in our stories,” she said in an interview.

She recently spearheaded the creation of the Crowd-Powered News Network, a venue for journalists to share ideas.

Jim Schachter, vice president for news at WNYC, said the engagement levels seen in crowdsourcing help the station get grants and bolster its outreach to donors.

Within the news industry, however, we think wider systemic adoption awaits more than enthusiasm from experienced practitioners and accolades from sources who welcome contact. Ways of measuring the impact of engaging in crowdsourcing initiatives and analyzing its value to a newsroom must be further developed.

We ask, for instance, whether crowdsourced stories have more real-world impact, such as prompting legislative change, than other types of journalism do?

To that end, we advocate for more research and evidence exploring whether crowdsourcing can foster increased support for journalism. That support might take the form of audience engagement, such as attention, loyalty, time spent on a site, repeat visits, or contributing personal stories. Or it might involve financial support from members or donors, from advertisers who want to be associated with the practice, or from funders who want to support it.